|

Leonid MAC |

| home |

| View the shower |

| Mission Brief |

| Science Update |

| Media Brief |

| links |

|

Ray Johnson Air Force Flight Test Center Public Affairs

EDWARDS AIRCREWS ENJOY FRONT-ROW SEATS FOR LEONID

Dec. 03, 1999 -

EDWARDS AIR FORCE BASE, Calif. (AFPN) -- Sitting inside their cockpits

Capts. Jeff Lampe and Frank Lane owned a view that Bob Uecker certainly

would be jealous of. The two 452nd Flight Test Squadron pilots truly had

front-row seats for the heralded Leonid meteor shower.

Lampe and Lane belonged to a 25-man team from the Air Force Flight Test

Center here that ferried 50 NASA scientists to Europe and the Middle East to

study Leonid, a meteor storm that occurs only every 33 years.

From his EC-18 Advanced Range Instrumentation Aircraft, or ARIA, Lane said

that for two nights he witnessed a "stream of shooting stars" during a

natural light show that garnered a global audience.

"However, they were brighter than what people saw from the ground because we

caught them entering the atmosphere," Lane said. "The meteors would pretty

much streak the full length of the sky."

Besides the ARIA, Edwards also supplied a modified NKC-135E tanker tagged

the Flying Infrared Signature Technology Aircraft, or FISTA. The pair of

aircraft served as observation platforms for cameras and scientific

instruments used by a crew of international astronomers. And by all

accounts, the researchers got what they came for -- especially on the last

night of the eight-day journey.

On Nov. 18, as the party headed from Tel Aviv, Israel, to Lajes Field, the

Azores -- a small island several hundred miles off the coast of Portugal --

Leonid showers comprised of sand-grain sized dust and ice pellets peaked.

Scientists, watching television monitors and wearing virtual reality goggles

with which to count stars whooped with joy in several different languages as

roughly 2,500 meteors blazed hourly in dark skies above the Air Force

planes.

"I heard 'wow' in Japanese, Dutch, German and English," said Jane Houston of

the California Meteor Society. "Everyone was energized at the amazing

images."

From his FISTA, Lampe said he spotted streaks appearing everywhere.

"While you usually see one shooting star at a time, we saw five over here,

five over there and so forth."

Dr. Peter Jennisken, chief NASA scientist for the Leonid mission, called the

night "fantastic and gorgeous."

"There were 78 beaming faces, researchers and aircrew alike," said

Jennisken, who works at the NASA Ames Research Center, Calif.

The airborne observers, however, weren't the only enthusiasts surveying

fireballs. From Hawaiian mountaintops to Arabian deserts, trained

astronomers and ordinary stargazers alike soaked in the celestial light

show. Because Leonid, which is debris from the Tempel-Tuttle comet, occurs

only once every three decades, it's easy to understand the curiosity and

excitement.

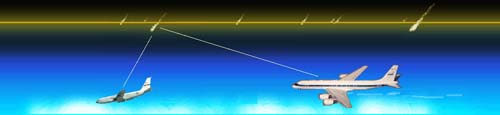

With the two Edwards jets, the 18,000-mile mission probably provided for the

most studied meteor storm in history. Flying in parallel formation at about

30,000 feet and 100 miles apart, FISTA and ARIA gave the researchers a

stereoscopic (three-dimensional) view, said Lampe, who served as the Leonid

task force commander as well as piloting FISTA.

Jennisken applauded Lampe's team for changing course toward several meteor

sightings to provide prime viewing for mid-infrared, near-infrared and

visible spectrograph imagers.

Jennisken also appreciated that the ARIA aircrew sent live video feed to

various research centers throughout the journey -- a first, according to

Lane.

Normally, ARIA uses a nose-mounted radome to record and store telemetry from

space vehicles and missiles. For Leonid, it downlinked real-time data via a

satellite system to NASA and Air Force Space Command ground sites. Some of

the imagery was immediately broadcast on television and various Web sites.

And because of FISTA and ARIA, NASA researchers captured two different

phenomena for the first time on film and through instrumentation, Lane said.

One was the relation between incoming meteors and thunderstorms, and whether

there's any electrical discharges between the two. The other phenomenon is

persistent train, a sustained light that trails shooting stars entering

Earth's atmosphere. Usually, a brief meteor glow called a wake lasts one to

10 seconds. For Leonid, they can last up to 30 minutes.

With such information now collected, Lane said NASA researchers will try to

determine upper atmosphere winds by measuring how the trains dissipated and

how they were contorted.

And "to top it off," said Jennisken, his crew observed some sprites, upward

lightning that some researchers believe is triggered by meteors.

|

||