|

Leonid MAC |

| home |

| View the shower |

| Mission Brief |

| Science Update |

| Media Brief |

| links |

LEONID DAILY NEWS: November 8, 2000

The two images on this page are snapshots (single video frames) of a bright Leonid meteor, showing twirling jet-like features.

SPIN CITY

Meteoroids are often thought to melt into a nice droplet and gradually evaporate their

consituent atoms.

Wrong! During the 1998 Leonid campaign, A. G. LeBlanc and Ian Murray

and colleagues of Mount Allison University, Canada, discovered that bright Leonids in

regular white-light video images tend

to have jet-like features sprout in all directions from the meteor head during flight.

This result was published in a recent paper in

"Montly Notices of the Royal Astronomical

Society" (Vol. 313, L9).

The jets form in a single video frame (< 0.033 s), which requires extreme velocities of

tens of km/s, a significant fraction of the speed of the meteoroid itself.

LeBlanc et al.

proposed a rather exotic explanation for the cause of these "jets":

electrostatic forces might cause small lighting flashes

during the meteoroids descent.

Wrong again! Now, Mike Taylor and co-workers have

proven that the jets are caused, rather, by small bits and pieces of the parent meteoroid

that are ejected at very high speed. Writing in an upcoming issue of "Earth, Moon and Planets",

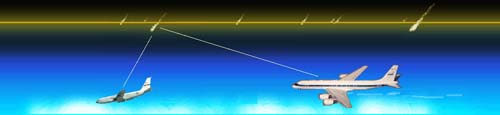

Taylor reports on observations with an

intensified CCD camera onboard the "ARIA" aircraft in the 1999 Leonid Multi-Instrument

Aircraft Campaign.

Leonids are known to fall appart in fragments early on in their trajectory

resulting in, for example, the flat-topped light curves (see

Oct. 30 news). These fragments will stay together if little momentum is transfered

to the grains. However, marked curvature in the jet-like structures suggests that the meteoroids

are rapidly spinning. This might well contribute to the occasional fragment ejection.

This result is of particular interest to Astrobiology, because the fragments are ejected

quite far from the meteoroid head. Hence, the amount of air that can be chemically altered

by the meteor is significantly larger than thought before

(Full paper -PDF).

Nov. 08 - Spin city Nov. 07 - Meteors affect atmospheric chemistry Nov. 06 - Listen to this! Nov. 04 - Fear of heights? Nov. 03 - The pale (infra-red) dot Nov. 02 - Twin showers Nov. 01 - Leonids approaching Earth Oct. 31 - Prospects for Moon Impact Studies Oct. 30 - Comet dust crumbled less fine

| ||

Taylor tuned his camera to the light of one specific atom: Magnesium.

This atom is part of the meteoroid and produces a bright green emission line at 517 nm.

Images of the meteor in this particular green light show the "jets" to be

turbulent structures that form very quickly. The material responsible for these

wirls must contain Magnesium. Magnesium is part of the core olivine and pyroxine

minearal silicate compounds. Hence the new explanation:

tiny fragments of the meteoroid are being rapidly ejected

away from the core meteoroid.

Taylor tuned his camera to the light of one specific atom: Magnesium.

This atom is part of the meteoroid and produces a bright green emission line at 517 nm.

Images of the meteor in this particular green light show the "jets" to be

turbulent structures that form very quickly. The material responsible for these

wirls must contain Magnesium. Magnesium is part of the core olivine and pyroxine

minearal silicate compounds. Hence the new explanation:

tiny fragments of the meteoroid are being rapidly ejected

away from the core meteoroid.